Physical Environment Flora and Fauna

‘Some 500 species of plants grow in the Torndirrup National Park which is less than 4,000 hectares. For such a small coastal area the range of vegetation types shows unusual diversity … From a distance the vegetation appears to be composed of low heath or stunted woodland, yet there are groves of very old trees with enormous girths to their weathered trunks …‘The diversity of plants is largely due to the variety of areas where different vegetation types can grow. The plant communities often indicate the underlying soil structure and type. Thus Peppermint, Woolly Bush and Acacia Littorea are mainly associated with the alkaline sands derived from weathered limestone. Open woodlands of Holly-leaved and Slender or Coastal Banksia, containing patches of melaleuca shrublands and interspersed with eucalyptus thickets, are generally over deep sand. Areas of low Oak-leaved Banksiaheath occur in less well-drained localities. Swampy bogs contain distinct plants like the Swamp Banksia and the Albany Bottle brush and the insectivorous perennial, the Albany Pitcher Plant. ‘ Vic Smith, (1991: 19)

Wildflowers

During the wildflower season (September to January) the usually undifferentiated heath around Torndirrup and Frenchman Bay becomes first a mass of white and yellow flowers followed by swathes of blues, purples, oranges, reds, and pinks – the magnificence and timing of each season is dependent on the climactic conditions of each year.

Challenges and Threats

With 143 species identified as under threat of extinction in WA, about $1.6 million was allocated in 2012 to WA’s Natural Resource Management programme for critically endangered flora recovery. It is considered that unless timely conservation action is taken, many of these plants are estimated to have a 50 per cent probability of extinction within the next 10 years. Measures to establish new populations and to control invasive weeds, feral animals and disease are some of the strategies used to conserve these precious species into the future.

The impact of Phytophthora cinnamomi (dieback), aerial canker, loss of habitat, commercial exploitation, inadvertent recreational damage, changing fire regimes as well as the potential ravages of hydrological change and climate change/variation, challenges and severely impacts ecosystems and the survival and interactions of species within them. In a recent survey of Albany’s vegetation status it was stated with regard to the significance of climate change:

Fauna

Sea Life

Sunfish

Sunfish are an oceanic species found at depths of up to 300 m. The biology and ecology of sunfish is poorly understood, presumably because individuals have an inaccessible distribution and are rarely observed near land, and also because they are not fishery targets and have low commercial value. However, visitors to Frenchman Bay can sometimes see the corpses of these strange-looking fish on Goode Beach and Whalers Beach in early winter (top images). More than a hundred of these fish litter the beaches in some years. Why is this happening?

PhD researcher, Marianne Nyegaard (Murdoch University) is studying the aggregation and mass stranding of Elongate Sunfish (Ranzania laevis) along the south coast of WA. Stranding events have been reported since the 1920’s but the cause of the strandings is as yet unknown, although the impact of strong El Nino conditions on the Leeuwin Current may play a role. Marianne’s research is ongoing and she is very keen to have input from our local Goode Beach community. She can be contacted at M.Nyegaard@murdoch.edu.au.

Sea Slugs and Sponges

Many people have never seen a live sea slug (or ‘nudibranch’’ the scientific name) or, for that matter, a live sponge in natural underwater habitat. Yet these animals are astonishingly colourful and varied. They live in Frenchman Bay and only intrepid divers are able to appreciate the visual effects. Among the sea slugs (molluscs without a shell) there is a vast variety of body shapes and patterns. Because they have no hard, protective shell they have developed other protective measures such as the capacity to secrete distasteful substances to deter fish, or can rapidly camouflage their bodies. Their vivid colours signal to predators that they are dangerous to eat. If you see them while diving it is best not to touch them.

Land Life

Yellow-Nosed Albatross

Albany is home or port-of-call to many seabirds. Perhaps the most magnificent is the Albatross. One species that visits Albany is the Yellow-nosed Albatross. One recently landed exhausted on Goode Beach and remained stationary even when approached by humans. Fearing that the Albatross would be attacked by a dog or by other seabirds, it was carefully taken home. The Albatross did not struggle, and although a large bird, it seemed almost weightless.

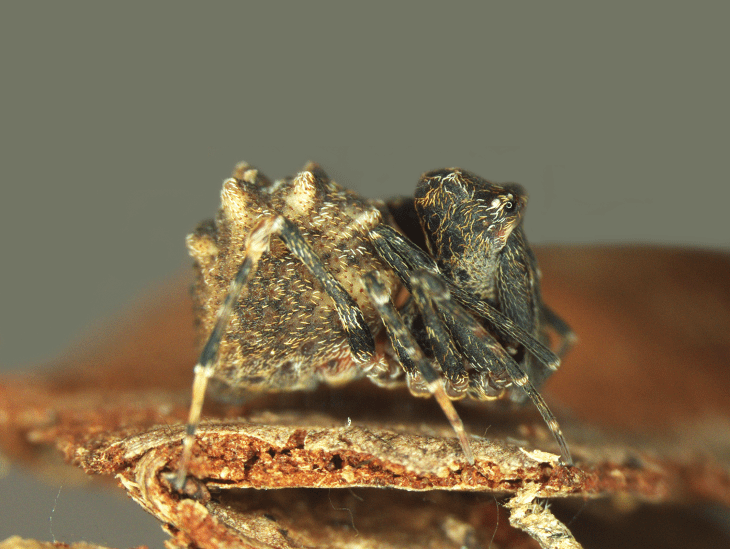

Photo courtesy of Mark Harvey, Western Australian Museum

Assassin Spider

The tiny Assassin Spider (Zephyrarchaea mainae) is a member of a spider-eating group of spiders known as Archaeidae and until recently was known only from fossil records. Some had been preserved in amber. They were unusual with thin elongated necks and long jaws lined with peg-like teeth. In 2008, Assassin Spiders were discovered near Albany. It is small spider (about half a centimetre in size) of a brown colour and hard to detect in the leaf litter where it makes its home. While found at Frenchman Bay, the Assassin Spider is also located at Bremer Bay and in rainforests in Queensland and New South Wales. Harmless to humans, the Assassin Spider hunts other spiders – hence its name.. At night it suspends itself from a single strand of silk and waits for other spiders. When one is within reach, the Assassin Spider spears its victim with its long jaws.

Rosenberg’s Monitor (top middle)

Rosenberg’s Monitor is the largest lizard in the Frenchman Bay area; adults have been known to reach 1.5 metres in length. The lizards have distinctive charcoal grey bands around their bodies and long tail. Their legs have speckled white spots. The monitors have sharp teeth to hold their prey. They should not be handled. They are relatively common and can sometimes be seen basking in the sun on bush tracks. It is possible, sometimes, to approach them to within a metre or so. The monitors will eat almost any animal of a size that can be swallowed. In the photo below, a large monitor has seized a young rabbit. Within a minute of the photograph being snapped the monitor had flipped the rabbit and swallowed it whole, head-first.

Southern Carpet Python

The Southern Carpet Python is found throughout Frenchman Bay. Adults reach two-and-a- half metres in length. It has a striking pattern. Colours vary from greenish brown to a blackish brown. The pythons feed on small mammals and birds and are mainly nocturnal. They are not venomous. Residents at Goode Beach have found pythons in their back yards and sheds. They may be approached and some submit to being handled though others hiss and strike when disturbed. Owing to predation by foxes and feral cats, and land clearing, the python is now gazetted as a threatened species. There have been instances where and motorists have run them over while they crossed a local road.

Tiger Snake

Most humans who are bitten accidently tread on them or near them. Bush walkers should keep on the tracks and not tramp through bush where there is limited visibility at ground level. There have been a number of dog fatalities in the Frenchman Bay area caused by dogs unable to resist investigating the movement of a tiger snake they have encountered.

Major References

(2010) E.M. Sandiford and S. Barrett, Albany Regional Vegetation Survey: Extent, Type and Status, South Coast Natural Resource Management Inc. and City of Albany for the Department of Environment and Conservation.

(1991) Vic Smith with Michael Bamford (illus.)., Portrait of a Peninsula: The Wildlife of Torndirrup, Wallace Smith.

Photographs

*Photograph of Little Blue Wren in shrubs affected with Dieback, taken by Sally (lillepod), Flickr Commons available at:http://www.flickr.com/photos/64250623@N08/6663914435/in/photolist-b9SiAt-e1Y3fM-d63VCf-hFzXUn-d6d9CU-9x7ogV-e4eh6e-81e4GM-7JVUzp-8Sp2Se-dvwC2N-dvqW58-duSEw5-8R1fk2-9T7NHi-ifNSwA-ifNSt9-ifNSvJ-duLVGc-duM1QD-9TaBK1-9T7NJc-dkW2Mb-9VcsPM-csmoLS-csmoZw-ejAxoT-9Gw3U3-88GvS5-8xoTxc, under license: Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivs 2.0 Generic

**Photograph of Banksia brownii plantings by Sarah Barrett DEC, Flickr Commons, available at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/71670801@N06/7933434314/in/photolist-d63VCf, under license: Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivs 2.0 Generic

Notes

[i]‘It’s an ongoing cycle of collecting the seeds from the bush; storing them in the seed bank; germinating a portion of in seeds in the lab; and then re-introducing the seedlings into a safe environment with ongoing monitoring systems in place to ensure their survival.’ Information also derived from the caption associated with the photo by Sarah Barrett (DEC) attributed above. See: http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/09/06/3004291.htm

[ii] DEC, [media statement], May 9, 2012 ‘Rescue Effort for Critically Endangered Flora’

[iii] Department of Environment and Conservation. (2009). Blue Tinsel Lily (Calectasia cyanea) Recovery Plan, DEC, Western Australia; and http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/publications/recovery/calectasia-cyanea.html

[iv]http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/publications/recovery/i-uncinatus/index.html