Physical Environment Flora and Fauna

An Early Puzzle: Coral on top of Bald Head

Bald Head, dominating the entrance to King George Sound, was named by Vancouver in 1791. It was visible to the early seafarers ‘from 14 leagues out to sea’. Bald Head has retained its name and is often referred to by early visitors to the Sound in their journals. Vancouver appears to have hiked to the end of the peninsula (later named Flinders Peninsula) as he observed in his diary the existence on the peak of Bald Head of ‘coral’. ‘Nowhere have I seen it so high up and so perfect’ he wrote in his journal. This seemed to him evidence that the over many years the sea level must have fallen. The so-called ‘coral’ became a matter of fascination among the scientists who followed Vancouver’s expedition. Later visitors thought it might be petrified tree parts. Francois Peron, a naturalist on Baudin’s expedition, thought that the coral or petrified trees sections were in fact ‘more or less hard sandstone, which preserves merely the shape of the plants that served them as moulds’. They were not genuine fossils. Further, contrary to Vancouver, the French scientists interpreted the evidence as showing that the sandstone peninsula leading to Bald Head had risen from the floor of the sea. It must have been a ‘peaceful upheaval’, according to Peron. Captain King, who visited King George Sound in 1818 and obtained specimens of the material, was of the view that the material was ‘merely sand agglutinated by calcareous matter’, essentially agreeing with Peron. De Sainson and Gaimard, officers on d’Urville’s Astrolabe, wrote that on their visit to the top of Bald Head in 1826 they ‘did not find the faintest trace of any coral’. However, they did report that the top of Bald Head was ‘pocked with meteors’, a rather dubious claim.

To put matters to a temporary rest, none other than Charles Darwin in 1836 made the trip to inspect the limestone material and provided a detailed explanation in his account The Voyage of the Beagle. It was largely consistent with that of Peron and King. Interest in fossils, geomorphology, and variations in fauna and flora produced the intellectual ferment that eventually led to Darwin’s groundbreaking The Origin of the Species published in 1859.

Fresh Water Springs

Visiting whalers and sealers would have continued to use the ‘Vancouver Springs’ during the 19th Century as it was available at any time of the day or night, all year round and free of charge. The early seafarers collected the fresh water from the stream as it entered the beach. It is thought that the first dam was constructed in the 1850s – amounting to little more than an excavation on the side of the escarpment immediately below the emergence of the spring.

During the second half of the 19th Century, the demand for fresh water began increasing as Albany town grew. The Peninsular & Orient Company (P & O) won the sea-mail contract across southern Australia. In order to supply the water requirements of their fleet, P & O built a dam at ‘Vancouver Springs’ to form a reservoir with a reliable and sustainable supply from which lighters would fill up and take water to their steamers. The water from Vancouver’s Spring was preferred because of its purity. They could not risk using water with mineral contaminants that would corrode the boilers.

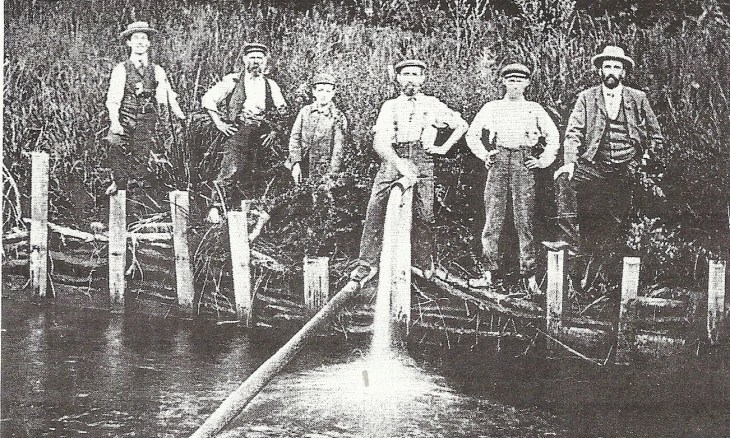

From about 1890 to 1902, Albany’s water supply was insufficient to meet shipping demands. As a result, in 1902 Armstrong and Sons acquired a lease for the section of Frenchman bay containing the old P & O Dam. They refurbished the dam and constructed a jetty at the beach. Water was pumped from the dam through a pipeline that ran to the end of the 200-foot jetty seen in the photo to the left.

Armstrong was contracted to supply water from Vancouver Dam to the Town of Albany and various types of shipping (including Boer War transports) until about 1912. By 1914, Albany’s water supply had improved and the Frenchman Bay supply was only occasionally required for shipping purposes.

The jetty and pipeline to water lighter circa 1902 Although the Norwegians dug two wells they also used Vancouver Dam for both a potable and process water supply – by installing a pipeline along the beach from the dam to various areas of the whaling station.

From the 1920s to the 1980s, various tearooms; chalets; and caravan parks were established above Whalers Beach and used the Vancouver Dam reservoir as a water supply until a bore was drilled above the beach in the late 1980s. Even when the mains water supply from Albany reached the Goode Beach area in 1983, people still collected water from Vancouver Spring for various domestic purposes (including tea making), because of the purity of the water compared to the scheme water!

Wrecks

Wreck of the Runnymede

The Runnymede was a wooden whaler built in Hobart in 1849. She was driven ashore by strong winds and wrecked in Frenchman Bay in 1881 alongside the wreck of the Fanny Nicholson that had been blown ashore nearly a decade earlier. These events were reported in the Hobart Mercury at the time.

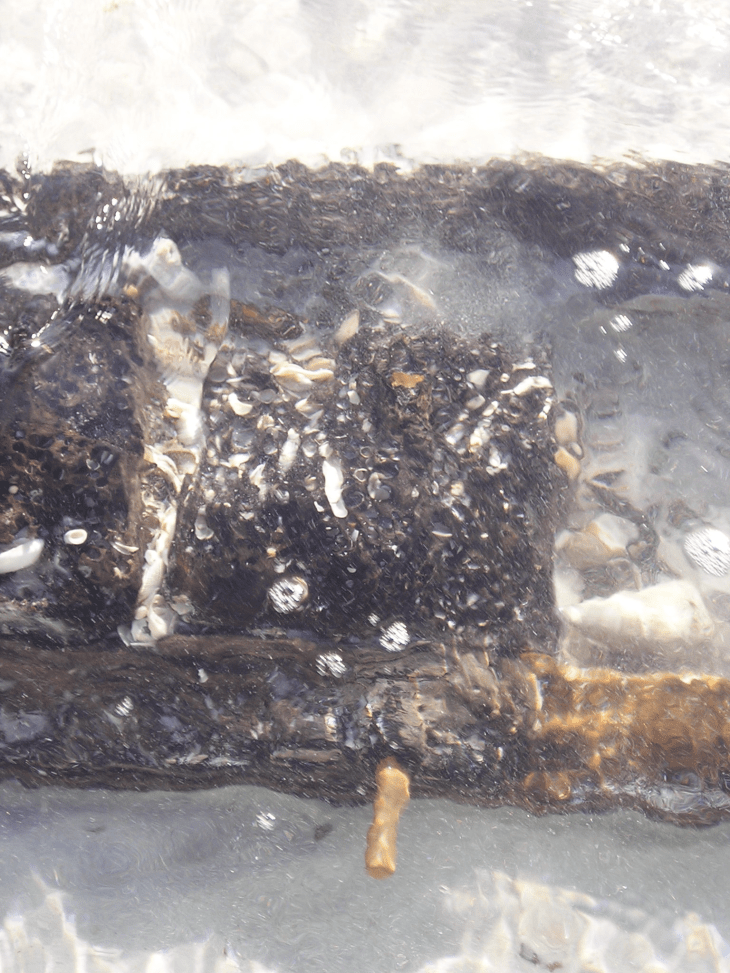

Sections of the hulls of the two vessels are occasionally uncovered after huge volumes of sand are swept away. Identifying the wrecks has turned out to be a challenge even for the experts. If the two wrecks are the Runnymede and the Fanny Nicholson then it is unclear which is which. It is even possible that one of the wrecks is that of a third vessel.

Fortunately, the remains are likely to be well preserved while they sit under tons of sand. Exposure to the air would cause them to quickly disintegrate. Every few years, under the right conditions, it is possible to catch a glimpse before they are totally hidden from view.

In this second, close-up photo the twin planking of the hull can be seen to be held together by brass dowels.

Wreck of the Elvie

In the 19th and early 20th Century small vessels known as ‘lighters’ were used to haul cargo and supplies to and from ships anchored in Vancouver Sound. These flat-bottomed craft sat low on the water were not powered: they had to be towed by larger vessels. Some were crudely made; they were basically workhorses. One such lighter was the Elvie whose remnants are still visible today on Whalers Beach.

The Elvie was built in Fremantle shipyards in the 1890s from local jarrah timbers and was licensed in 1903.

In 1915 the Elvie was sold to the Norwegian Spermacet Whaling Company to transport barrels of oil from its shore station in Frenchman Bay to ships anchored in deep water. The lighter left Fremantle in June 1915, towed by the Company’s whaling steamer, the Klem. The lighter had a short working life in Albany since the whaling station closed some months later. The Company salvaged some of the most valuable factory equipment and shipped it to its station on the northwest coast at Point Cloates but left behind the Elvie and another lighter, the Fran.

In 1921 a gale blew the Elvie and the Fran ashore. The Fran was eventually lost from sight but the Elvie was lodged on the beach at its present site. In the 1922 photo an Albany resident, Mrs Hartman is shown sitting on the side of the intact hulk.

A degree of protection from vandalism was provided by the remoteness of Whalers Beach; a road was not constructed until 1928. Unfortunately the remains of the vessel were progressively pillaged for firewood and most of the above-ground structure disappeared. The lower sections were preserved under tons of beach sand, though occasionally revealed after heavy storms. One such storm in 2002 exposed a section of the hull and shifted it along the beach. Residents at Goode Beach recovered the section, preserved it, and installed it above Whalers Beach as shown in the photo to the left. The rough-hewn jarrah ribs are clearly visible.

Over the years there have been several archaeological examinations of the wreck. The photo below shows the exposed timbers at the time of an archaeological examination in 1991.